NEIT Master of Science Program Development Case Study by DJ Johnson

Background Information

After conducting conversations with industry leaders and their mid-level managers, it was observed that the younger generation of professionals are adept at acquiring and maintaining their core discipline, but they lack the confidence to be open and effective when it comes to dealing with disruptive technologies and business trends. With the fast pace of innovation and global competition, it’s crucial to have a workforce that is agile in the realm of Human Centered Design (HCD).

This case study will focus on the process of designing, developing, and approving a Master of Science degree that delivered HCD in the framework of an interdisciplinary technology program.

In 2017, NEIT received approval from the New England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC) to underwrite master’s degree programs in the domain of science and technology.

The reader will understand and appreciate the scope of the development undertaking and the tangible value of Applied Design as a universal skillset that spans the entirety of the New England Institute of Technology (NEIT) degree spectrum.

NEIT Approved for Advanced Degrees

To achieve this standing, a sample of MS degrees were piloted in disciplines such as Information Technology, Building and Technology, and Occupational Therapy. The preliminary program proposal for the Master of Applied Design (MAD) was used as a test case to verify the tolerance of NEASC’s decree for disciplines that were not as obviously science or technology-oriented. The accrediting body accepted the MAD proposal as a valid advanced degree. This accreditation expanded the brand and potential of the career-oriented college, giving it standing with other well-known regional universities.

A working group of this author, DJ Johnson, and Dawn Edmondson, with the oversight of Sheila Palmer, was convened to build the MAD curriculum following the NEIT program development process. This team originally came together as members of the Faculty Development Committee, and each of us had a strong track record of creative problem-solving and multidisciplinary collaboration. It was an ideal team for such a unique program. The primary champion of the project was Assistant Provost Henry Young.

The Risk and Reward of Master of Science Degrees

While there was plenty of evidence that higher education institutions like Harvard, MIT, and Georgia Tech to name a few, were catching on to the demand for a managerial workforce that could “fail fast” and “disrupt disruption” it was still very early days for the smaller, less-endowed private universities of New England. We built this concern into our design challenge question:

“How might a rising star institution like NEIT design an MS curriculum that would deliver creative and agile innovators that also had credentials in the realm of business strategy and management?”

In addition, we challenged ourselves to answer how we might position NEIT to successfully market a unique MS program and achieve a reliable enrollment level to support the full-time and adjunct staff of professionals that would be required to deliver a consistent and valuable outcome.

There was a clear need to build the curriculum to meet the NEIT brand and what we perceived as the appetite of NEIT alumni who desired a master’s degree that was rewarding professionally and without any financial or professional risks.

Human-Centered Design as the Solution

We approached the challenge of a curriculum for professionals trying to meet the demands of an evolving and disrupting environment by using the principles we hoped to embed in the coursework: Discovery, Analysis, Ideation, Prototyping, and Testing. This approach was necessary because the number of similar programs we could reference was limited to a handful worldwide.

Note: Instructional Design professionals may recognize that HCD shares many elements of ADDIE. From my experience, all good design has an iterative mindset at its core.

Discovery

As with most curriculums we worked from the outcomes forward. We needed to ensure the graduate of this program had achieved a high level of creative confidence that they could mete out in whatever discipline they claimed as their primary. We began by modeling all fifty-five degree programs of the University based on the assumption that most of our candidates would be matriculating from their current bachelor’s degree program or returning NEIT graduates. This discovery process went quickly and immediately pointed to some important areas we could address with our curriculum. However, not all the answers jumped out at us. In-depth analysis was necessary.

Analysis

Our analysis required us to do a great deal of academic research across various resources. The data showed a trend toward the outcomes we had selected as our goals, but it also showed the nascent concepts of HCD and Design Thinking were not deeply studied. We turned to ethnographic interviews of graduates, professors, and a great many industry professionals who spelled out what they were looking for in a person holding a degree of this sort. The spectrum of answers inspired more courses than any MS candidate would be willing to shoulder. We had to focus our course selections down to a menu of eleven. We did this through brainstorming.

Brainstorming

Bias is always a factor when a team approaches brainstorming. As a nascent science, Human Center Design was idealized as a “fix anything” skill set. We had the advantage of a wide-open whiteboard of opportunity, but with that came the risk of confirmation bias, which could lead us into a “Wonderland” of good intentions but poor academic and professional value.

We addressed this by iterating from a free-for-all of ideals down to a rigorous standard of values. In addition, we were challenged to incorporate critical benchmark MS courses in logic and management from other degree programs like IT and MSEM. The tension of these practical methodologies forced us to lean into the ambiguities inherent in a methodology of creative innovation. The work rendered a scaffolding of practices that were equal parts inductive and deductive reasoning resolved by tried-and-true standards and practices.

The next step required detailing the courses through the practice of low-fidelity to high-fidelity prototyping.

Prototyping

We used our team’s unique mix of creativity, drive, and persistence to develop each course outline. Whoever was lead on the course was designed with a bias toward the stated outcomes. The other two team members observed and commented with a bias toward engagement and investment. We all had a considerable portfolio of diverse course development work in our primary disciplines. We naturally moved the lessons from introductory knowledge to reinforcing experience to mastery at a level that could be sustained through a career. We also had the support of a team of talented instructional designers (IDs) from the Office of Teaching and Learning. The IDs cast a critical eye on the coursework and courseware to ensure it performed well. With that considerable amount of work completed, we moved into live testing.

The New England Institute of Technology design team guided Dawn and I through the process of drafting and polishing the Applied Design courseware. I owe them a great deal of my confidence and skill as an instructional designer.

Testing

Our experience has been that at best, only eighty percent of course design is predictable. The remaining twenty percent is subject to variables that cannot be known until the materials meet the target audience. We sought every opportunity to test the concepts and lessons we felt most critical to the curriculum’s mission. Sometimes, we accomplished this by presenting to colleagues, and sometimes, we made advances by incorporating elements into courses we were teaching in other disciplines. These efforts were fruitful and sometimes caused a re-design of lessons, labs, or courses accordingly.

This process helped us imagine and template six new courses in six months. Four of those courses were presented to and accepted by the curriculum committee, ensuring we had a solid baseline for the program launch.

If you build it…

From start to finish, it was a two-year adventure in conceptualization and construction. As a team, we had confidence that we had designed a program that would be engaging and valuable to a community of leaders seeking a non-typical educational experience.

We also earned the support and respect of the various educators and professionals we interacted with to bring the program together. Upon the approval of the Provost and President, the registrar assigned the program course numbers and put in a schedule for the Fall Quarter (2018). Marketing sheets were printed, and the admissions team went to work spreading the word.

Unfortunately, all the Masters’ programs of the University struggle to find their marketplace with the limited resources that are being jealously consumed by the 55-plus programs across the campus. A master of science in applied design was a heavy lift bearing in mind that discipline was so unique and atypical program. In addition, the program launched at a time when the consumer appetite for master’s degrees became less reliable.

Word came down from OTL that the program needed to wait for a climate that would be more encouraging. Admirative resources were reassigned to the programs with a more well-established supply of ready applicants.

While we have no data, KPIs, or balance sheets to express the return on investment, I can say that I achieved many benefits from the collaboration across the college and the discovery process in the discipline. In short, HCD has been invaluable to me as a professor and professional.

Epilog

One course from the Master of Applied Design curriculum has been running for the last three years as part of the MSEM curriculum. The course is MAD 511 – Human Centered Design Thinking. The mechanical and electrical engineers who have taken it have given it high marks for being challenging and changing the way they look at problem-solving.

This is a comment from the most recent iteration of the class which ran during the summer of 2021.

“I personally enjoyed the process of embracing ambiguity in this class. It forced you to go outside of your comfort zone to develop ideas and designs that were not obvious initially. I also enjoyed the insight from the guest speakers and their explanation and applications of HCDT.”

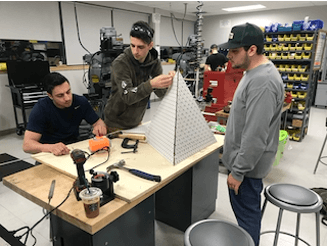

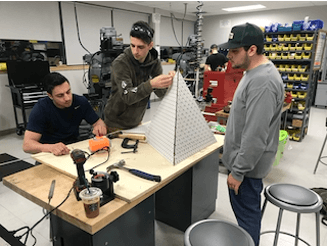

Two early prototypes of the program also run as part of the Engineering curriculum. ENG 100 Imagineering is an explorer course in Design Thinking for Sophomores. ENG 300 Human-Centered Design is a higher-level design course taught to seniors in the engineering curriculum by Dawn Edmondson. The course was cross-listed with the Interior Design curriculum and features engineers and designers collaborating.